POSTURE, SPORT AND THE ATHLETE

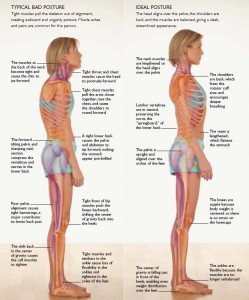

Every Athlete has a unique posture, with subtle idiosyncrasies, that make it unique as a consequence of a “normal” adaptation to a particular sport. Adding to this mix are, perhaps prior, injuries which have altered the posture as well. Furthermore and somewhat are other less intangibles, such as nutrient deficiencies (i.e. muscle weaknesses & nutrient relationships), nerve entrapments (i.e. causing weak muscles); are just some of the more “less” applicable variables that could possibly alter posture.

Athletic movement is a series of sequenced individual segments linked together to form a chain(s) (a.k.a. “kinetic chain”), which globally is represented by a number of dynamic postures. If, for an instance, a “segment” in this chain is repeatedly “off”, because of any of the reasons mentioned above, this can have potentially disastrous effects on the global posture (i.e. increased injury potential, performance decline), depending where and how big the segment is on the body. Therefore, it is imperative that the Regeneration Specialist / Coach, evaluate and address the potential segment(s) that may be out, and determine why they are that way. Instead of analyzing the dynamic posture, which is definitely a plausible avenue, energies would be better directed in addressing static posture and letting the body figure the movement out by itself….

“Create the “ideal” tension patterns for static posture and the body will go were IT needs to go based upon the best possible mechanical advantage IT determines to be optimal at that particular time. Therefore Regeneration and Conditioning work must address creating what we call “buffer zones” for abnormal tension patterns that the athlete may subject their body to.”

For example the axle on a Formula-1 race car can handle much more torque than the axle on a Ford Pinto (please refer to our previous blog entitled “Why you are not improving part 1 of 6). So if the athlete stands right, and as long as it is close to within 80 to 90% to ideal posture, “we’ll take it.”

“If it stands right, walks right, runs right, sprints right ….it must be Right”

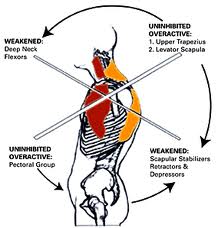

There are a set of Tonic muscles a.k.a. anti-gravity muscles:

- the gastroc-soleus group (superficial and deep compartment muscles),

- the quadriceps-adductor-hamstring group,

- the erector spinae-superficial gluteal-deep gluteal group,

- the transverse abdominal-obliques-rectus abdominal group, and lastly

- the rhomboid-pectoral-neck muscles group

which help to maintain the body’s vertical position under various static and dynamic conditions. The control of these particular muscles is another topic in itself, but let us go as far as to say it involves, and is limited to, four major sensory systems in the body: the proprioceptive, vestibular, integumentary (i.e. the skin) and visual systems. These systems are also part of a much larger highly integrated continuous fabric that is three-dimensionally woven into EVERY part of the human body, and is related to the motor cortex, but at the same time by-passes the motor cortex.

“If you seek it you can not find it, but you know where it is”

Conditioning must address this complex system, by enhancing its structural and sensory components, so that movements as simple as walking and as complex as sprinting, somewhat defy Gravity.

“Walking is considered to be a ‘controlled series of falls’. Therefore, optimal movement can be defined as the ease of movement into the next movement“

The sensory system, when working optimally, allows the “anti-gravity” muscles to work in a synchronous manner to help maintain joint structural integrity and allow for optimal efficient movement of the limbs. This is accomplished with a series of rapid limb positioning and repositioning, according to the nature of the activity undertaken by the athlete.

“The body moves its limbs on the premise of Anchor & then Move….you can not fire a cannon out of a canoe…unless you have pontoons”

Thus, a majority of human movement is executed below our sensory awareness and is at a sub-sensory level (i.e. below our conscious kinetic awareness). There are an infinite number of micro movements, roughly 48 billion bits of information per second, that are ‘perfectly’ co-ordinated to move the body through time and space, with the ‘appropriate’ of amount of energy required to support and execute a movement. The quotes ( ‘ ‘ ) are making reference to the fact much of the average human being moves inefficiently. On the other hand, elite athletes still have some inefficiency, however, it is considerably far less. As a coach, we must learn to identify and tighten the ‘leaks’ in movement using the appropriate conditioning tools, knowing that movement can not be emulated in the conditioning arena, but rather it is only made to withstand the rigors of the sport…i.e. extend mechanical breakdown.

“An elite sprinters leg moves roughly at a rate of 80 km/per hour, no exercise in the weight room, other than sprinting itself, can duplicate that velocity…..movement just happens, you can not contrive it”

Some would argue that those who try and determine muscle imbalances, and subsequently try and correct them via “Corrective Exercise”, are merely spinning wheels. We beg to differ, as every individual is unique in its make up, past injury history, etc… To this end we say…

“You are only as strong as your weakest link(s)’

It has been our experience that by addressing these weak links, more likely done on non-training days, in the form of ‘Exercise Homework” done by the athlete, the results are some times very spectacular. This is not to say that we do not execute contemporary conditioning methods, but rather weave these elements along with other elements simultaneously into our training regime. As the imbalances diminish, as a consequence of not only correct remedial exercise, but also due to the strategic application of much larger, compound movements; one set of exercises are relinquished as a new set are introduced. The program we set forth is very organic, yet the compass we set is always pointing towards better performance.

“The best coaches are the ones that make the athlete expend the least amount of effort, using the most appropriate exercise at the same, based upon the weakness / technical faults they encounter, to achieve the best possible results in the shortest period of time…. all methods are good…but it requires wisdom in how to use them….what can be bad for some, is actually good for others and vice versa”

As an aside, some muscle imbalances have nothing to do with that particular muscle, but rather are responding to inappropriate sensory queues being relayed throughout the body, due to numerous reasons, some of which we have mentioned earlier, and all of which fall into a hierarchical order, which can be completely different for every athlete.

Elite athletes, despite having small idiosyncratic movement deficiencies as a result of improper muscle length- tension relationships (i.e. strength and flexibility), result in minor movement compensations. However, due to their high degree of “physical intelligence,” elite athletes are also great compensators, as they have learnt to adapt and overcome, and therefore overcompensate for the lack of efficiency. Depending upon the degree of compensation, and whether or not the athlete is successful, sometimes it is best to let things be, and not to alter it, despite being what it is. It is important to be mindful and observant, that in a fatigued state, the compensations could potentially set the athlete up for a future injury,

therefore, as a coach, you must not let this happen. By-in-large, the body eventually heals itself after an injury, irrespective of therapy or no therapy. The body is hard-wired to heal, therapy may accelerate the healing, but do not lose sight, you are also dealing with a highly motivated individual that wishes to get better, plus you are dealing with a physiology that has been trained to regenerate at an expeditious rate. Having said this…

“It truly takes a really wise person to prevent an injury from occurring in the first place.”

If however, by addressing the compensations there is room for improvement, that could potentially spell-out about 20-30% extra performance, then it would be wise to address the inefficiency. This is a judgement call that has to made depending upon the situation.

SWIMMING & POSTURE

A majority of swimming coaches we have had the pleasure to interact with, seem temporarily absent of mind, with regards to recognizing that despite spending much time in the water, swimmers are bipedal land mammals. They try to make the athlete adapt to the aquatic medium, by ‘streamlining’ the athlete’s posture, via countless hours of repetitive cyclical movements. In doing so they, the coaches, create postural imbalances (see above picture), that appear very typical to all swimmers who fall neglect to addressing these imbalances with the appropriate dry-land conditioning regime.

Conditioning for swimming tends to fall greatly in either the prone (i.e. on your stomach) or supine (i.e. on your back) positions. Despite these positions being some what “sports-specific,” they are more geared for those athletes that are “posturally”challenged. Having said this, it is not to say that we do not utilize these positions, however, by conditioning in a more vertical position, provided that they are not too compromised in gravity, the athletes being to learn to activate particular reflex mechanisms that would not normally be activated if they were in the former two positions. Hence there is a greater activation of the “Anti-Gravity” muscles and the postural sensory system, via conditioning in the upright position. Despite less activation in the supine / prone positions, these muscles are still engaged, be it at a lesser degree, also factoring in the concept of “USABLE STRENGTH” (i.e. amount of strength maximally generated in the weight room via, for example a maximal squat, which is only roughly 80% of total Maximal Voluntary Contraction (MVC) that can be harnessed during an athletic activity). Getting back to the vertical position, it presents itself with a greater ability to dynamically involve the complex kinetic chains situated in the body. Generally speaking, if the athlete is more aligned vertically, they are more streamlined in the water.

Conditioning for swimming must therefore address the weak links, but it must simultaneously reconnect the “link” back the to whole chain. The midsection is the relay of sensory information as it is a generator of force. Sometimes we need to isolate, but we must then learn to integrate. On other instances, where there is no need for this reductionist approach, large movements by themselves engage the fullness of a majority of the kinetic chains. We make reference to this idea in the form of three types of conditioning phases in a previous blog article we mentioned earlier “Why you are not improving part 1 of 6”:

- STRUCTURAL FITNESS

- STRUCTURAL PERFORMANCE

- PERFORMANCE CONDITIONING

In conclusion, there are several steps a coach can take to provide him/her with meaningful information in designing a conditioning plan:

1. Determine the bio-mechanical and physiological need of the sport and event / position

2. Determine the bio-mechanical and physiological impediments of the athlete in question (i.e. injury history, health risk factors, biological vs chronological age, gender, body type (Ectomorph, Mesomorph, Endomorph), rate of regeneration, level of fatigue to name a few)

3. Time constraints – training part-time, training full-time, time to do extra un-supervised training on their own

4. Facility constraints – access to equipment, travel to and from the facility

5. Regeneration Accessibility – access to massage, sauna, contrast baths, etc….

If you liked this article you should also check out “Why you are not improving part 1 of 6”